Drawing attention: Putting a love for nature on paper

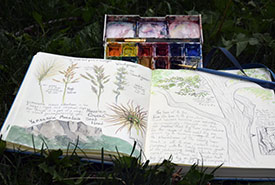

My nature journal entry on the plant life at Yamnuska Mountain, AB (Photo by Emma Dunlop/NCC)

Nature journaling; two words that I recently have noticed cropping up together, in everything from youth education curriculums to mindfulness and meditation workshops. My first encounter with nature journaling was during my reluctant participation in a school assignment in Grade 7. My English teacher sent us out into the woods to “learn something school can’t teach you.”

Despite my doubts at the time, the practice of nature journaling stuck with me, and has now become a part of how I exercise my love of biology to this day.

It wasn’t until I attended university that I realized I was a part of a time-honoured tradition that biologists, illustrators and conservationists have taken part in for decades. Now, as nature journaling makes its way into the public eye in new and exciting ways through education curriculums and mindfulness workshops, it is worth taking a moment to describe what it is, how it’s done and what it can do for you.

What is nature journaling?

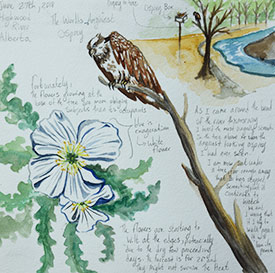

My journal entry on June 27, 2018, on the flowers and osprey I observed at Highwood River, AB (Photo by Emma Dunlop/NCC)

As the name implies, nature journaling is the recording of observations of nature. The range of possible subjects for a nature journal are as wide as the biosphere is diverse, as all living things and their context are part of what makes up nature. The medium can range from drawing, to prose, to poetry, or anything in between, in any combination. How you record your observations is personal preference. What matters is your willingness to dedicate time and attention to producing a genuine recording of nature — as you, the journalist, observed, thought or felt about it.

The keys are taking time and paying attention to details. They are what make nature journaling such a valuable exercise, as it is through their application that you build an understanding and feeling of connectivity with the object of study. At the same time, the journaling process helps you develop mindfulness and gives you the chance to reflect.

With a nature journal, you can track changes over time, either in nature or in your skills and perceptions. When you take the time to carefully observe some aspect of your natural environment, you learn about it. When you write about it or draw it, you learn something about yourself, about the way you perceive nature. In both cases, people who practice nature journaling develop a deeper and more caring relationship with their natural environment.

Who nature journals?

Painting with watercolour (Photo by Emma Dunlop/NCC)

With this in mind, it is not surprising that many famous conservationists were also nature journalists. John Muir, sometimes referred to as “the Father of the National Parks” in the United States, was an avid recorder of nature observations in the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range and Yosemite National Park. Aldo Leopold’s The Sand County Almanac, an important text in the modern conservation movement, is a work of curated nature journaling. Anna Botsford Comstock made a life’s work out of bridging the gap between scientific investigation and personal experiences gained from interactions with the natural world. Even Henry David Thoreau, writer, philosopher and conservationist, wrote and illustrated with nature as his subject.

But nature journaling is not just for the great and noteworthy. Nature journaling can be an enriching part of anyone’s outdoor experience. Best of all, there are no limitations or expectations about what your nature journal should look like or have in it. Your nature journal, your way.

Here are four easy steps to get started on nature journaling:

1. Get the tools of the trade

My trusty watercolour set and notebook (Photo by Emma Dunlop/NCC)

In order to journal, you need a journal and some writing instruments. This can be as simple as sheets of paper and a pen. If you feel like jazzing it up, use coloured pencils or even watercolor paints.

2. Set aside time exclusively to nature journal

Life is busy and full of distractions. All the more reason to dedicate time to focus on watching and listening rather than doing and saying. Remember: Time and attention are the only two things you need to bring to nature journaling.

3. Head outside

Get out into nature and journal with the time you have set aside. It doesn’t matter if it’s a public park or an isolated mountain peak.

4. Be curious and kind to yourself

Make nature journaling a labour of love. Focus on something that catches your eye or imagination. Be gentle with yourself if your journal does not turn out the way you were hoping it would the first time. Skill is a function of practice.

Drawing by Rayma Peterson

The Conservation Internship Program is funded in part by the Government of Canada’s Summer Work Experience program.