Women in conservation: Kathryn Folkl

Kathryn Folkl (Photo by NCC)

In honour of International Women’s Day (March 8), we’re celebrating eight female conservationists at the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) who are working to create a stronger future for Canada’s landscapes.

Growing up on the rocky shores of Lake St. Clair in southwestern Ontario, Kathryn Folkl has been immersed in nature her entire life. From the swarms of burrowing mayflies under every lamp post on the suburban streets near her childhood home, to her current position as NCC’s national manager of the North American Wetland Conservation Act (NAWCA) program, she’s been drawn to nature, much like the familiar bug from her past to a bright light.

Kathryn Folkl (Photo courtesy Kathryn Folkl)

Her academic career began in the environmental science program at the University of Guelph. After a quick detour into the fine arts (acting) program at the University of Windsor, she was back on the environmental track, eventually leading her to a master’s degree in plant ecology from the university where her academic journey first began.

Read my interview with Kathryn below:

RB: What is one of your first memories of nature?

KF: One of my first memories of nature was the sound of burrowing mayflies, commonly referred to as fishflies, crunching under my feet as I made my way to my school bus stop as May turned into June each year. I remember the cracking of their bodies and wings as my brother and I would try (unsuccessfully) to leap over the masses of bugs covering the road around the street lights.

RB: What was your first job in the environmental/conservation/science field? What did you learn in this position that has helped you now?

KF: My first job in science was as a bug counter. I spent many, many days inside a lab staring through a microscope, attempting to identify different species of aquatic invertebrates by their mouthparts. Chironomids are important as indicator organisms for pollution. The bug larvae I identified and counted were collected in wetlands near the Athabasca oil sands in Alberta. Not only were they somewhat terrifying to look at when magnified, they were also often covered in sticky tar, which made holding them with dissecting forceps challenging and identifying them sometimes impossible. After my first week, I would close my eyes at night and see chironomids floating through my dreams.

This position was my first introduction to sample size, the hands-on scientific method and how the collection of information really can impact your interpretation of the science results. As a result of this experience, I now look closely at the data collected by NCC and other organizations to see whether it will actually answer the questions we’re posing.

RB: Describe a typical day at NCC for you.

KF: I have one of two typical days: I’m either in an office staring at a computer screen with way too many tabs open, trying to ensure the pieces of land we’re securing meet both our conservation objectives and the broader continental conservation objectives for migratory species, or I’m at a meeting with external partners: leaders in conservation in government, industry and non-profits both across Canada and in the broader North American context, where I’m distilling the latest information on partnership opportunities to coordinate conservation efforts.

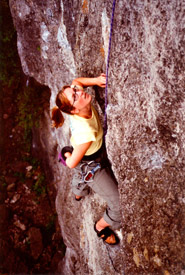

Kathryn Folkl rock climbing (Photo courtesy Kathryn Folkl)

RB: What do you consider your “best moment in science”?

KF: My best moment in science occurred when I was completing my master’s degree. I got to answer a question that really mattered to me, and it solidified the value of applied science.

You see, I was a rock climber, and recently published research had indicated that rock climbers were negatively impacting plants on the cliffs of the Niagara Escarpment, where I frequently climbed. As both a scientist and a climber, I looked quite critically at the primary literature to see how researchers had answered the question, “Does rock climbing impact vegetation on such and such cliff?” and was surprised when I saw how the question was being answered.

In various ways, researchers had statistically compared pristine cliffs to climbed cliffs and come to the conclusion that fewer and/or different species of plants were found on the climbed cliffs and attributed this difference to climbing disturbance. As a plant ecologist and a climber, I knew that other factors could impact a plant’s "choice" to be on one cliff versus another and, in fact, impacted a climber’s choice to be on one cliff or another. These factors hadn’t been included in the research.

Therefore, I designed my own study to answer the question, “What is the relative impact of microsite heterogeneity (the ledges, pockets, slope, aspect, etc.) of the cliff versus the presence of climbing on cliff-face vegetation?” and got a more complete answer. My research confirmed that fewer plants were growing on the climbed cliffs when compared with pristine cliffs, but also showed that this was not related to a climbing disturbance. Rather, climbers selected cliffs to climb that naturally supported different and less vegetation as a result of the physical characteristics of the cliff.

RB: Why is it important for women to be in science?

Science is how people understand and relate to the world around them. To be a leader, of any gender, in any number of fields, we have to understand how to ask a question, critically analyze the information available and synthesize an answer. Science teaches us how to be the experts, and to rely on our own critical thinking skills. It’s through science that we can ask the questions that we want the answers to, and challenge information we feel is incorrect.

RB: What advice do you have for women wanting a career in the science or, more specifically, the conservation field?

KF: I would advise women interested in the conservation field to do two things: (1) learn critical thinking skills; and (2) speak up! Conservationists tend to be introverts, preferring to commune with nature or with like-minded folks who share our wonder of the natural world. But we need to change the thinking of a broader audience to really achieve our goal of conservation. And that means sometimes having more challenging conversations. If you can understand the research, you should be a spokesperson for nature.