An intimate connection to nature

Norman Hallendy (Photo courtesy of Norman Hallendy)

For the last 40 years, Norman Hallendy has spent his life learning about the Arctic and the many Inuit people who call the land home. His deep interest in this area has brought him across the Arctic, studying different communities and their connection to nature and one another.

Norman Hallendy began his Arctic journey in 1948, at a time in which many Inuit peoples were moving from the land into permanent settlements.

His work in the Arctic and his role in interpreting the inuksuit earned him the Royal Canadian Geographical Society's Gold Medal in 2001.

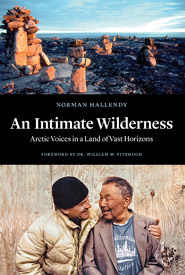

In his memoir, An Intimate Wilderness: Arctic Voices in a Land of Vast Horizons (Greystone Books, 2016), Norman writes of his adventures as an ethnographer in the far north, including wildlife encounters with polar bears, profound friendships and what it means to live alongside nature.

An Intimate Wilderness: Arctic Voices in a Land of Vast Horizons (Image courtesy Greystone Books)

Also an Arctic researcher and photographer, many of his talents are woven within the pages of his book, which is filled with stories about the people and the Arctic and illustrated with stunning imagery.

I recently spoke with Norman about what drew him north and how his bond with Inuit elders strengthened his connection to nature.

As a cultural researcher from Ontario working in the Arctic, Norman had to set aside his previous perceptions of how people live and work in these rural communities and open himself up to new experiences. By faithfully recording everything he saw, he was able to develop a better understanding of Innu culture.

“I had to put aside how I was taught to think, along with the beliefs, biases, opinions, and values I learned, shaped by the only material and intellectual culture I knew,” says Norman. “I had to learn the abandonment of who I thought I was and who I thought they were.”

According to Norman, one of the difficulties of living in the Arctic is dealing with the distance and remoteness of communities from the rest of Canada. Away from technology, residents of the Arctic live a different life than someone with easy access to electricity and a Wi-Fi signal. Instead, many residents of the remote north may be more intimately dependent on nature and the land than Canadians in the southern portions of the country.

Author Norman Hallendy with Inuit artist Kenojuak Ashevak (Photo courtesy Norman Hallendy)

“The Inuit perfectly adapted to their environment, ensuring not only their survival for more than 400 years, but the development and sustainability of a unique culture,” says Norman. “The expression ‘inuutsiarniq asini,’which means ‘living in harmony with nature,’ is an ancient and powerful metaphor.”

As Norman learned through his many interviews with Inuit elders, the Inuit are not only dependent on the land for survival; they have a spiritual connection to nature. This connection forms the foundation of their philosophy and shapes the way they see and care for the environment.

“[The Inuit] believe that [nature] is both a physical and metaphysical entity. It is a living thing,” says Norman. “To behold, respect and understand the forces and behaviour of the land, sea, sky and weather was the bedrock of their unique culture.”

From An Intimidate Wilderness, one develops a sense of looking at nature in a more personal way. By reading this book, you are immersed in a new way of viewing your surroundings. It opens you up to seeing nature, other humans and wildlife as a full circle rather than as individual elements.