There are bears on Prince Edward Island

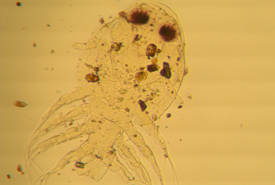

Marine tardigrade, known affectionately as a 'water bear'. (Photo by Emma Perry)

What’s that, you say? There are bears on PEI?

Yes! Well, sort of. Tiny, microscopic water bears!

I live in Prince Edward Island, the smallest Canadian province, with the highest population density. We have a long history of humans living on the island, which has led to the local extinction of seven mammals, including the more familiar American black bear, a species common on the east coast. Most large mammals require large habitats and/or isolation from humans to survive, and PEI just couldn’t support both humans and these species.

Crab larvae (Photo by Emma Perry)

So, what is a program director to do when there are no moose looking for a mate? Fortunately, PEI is still home to some interesting critters, if you’re willing to adjust your lens and think smaller. Much, much smaller.

In 2016, Dr. Emma Perry, a marine biologist and professor with a specialty in marine invertebrates, contacted the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC), as she was investigating potential study sites in PEI to look for tardigrades, affectionately known as “water bears.”

Tardigrades are tiny creatures ranging in size from 0.01 to 0.5 millimetres. Evolutionary biology shows us they are a “missing link” between worms and insects, as, unlike worms, they have tiny little legs with muscle fibres, but lack the formed musculature of a true limb in insects. They can be found in both terrestrial and marine environments, and are most well known for their ability to survive in just about any condition (space, radiation, strong acids, liquid helium, etc.). It’s important to recognize that tardigrades are not classified as extremophiles, as they did not evolve in these conditions, but can survive them.

While choosing a study site, Perry noticed that in all of the coastal ecoregions bordering Canada, there were no records for marine tardigrades. So, out of the two she could drive to, she chose Prince Edward Island (the Gulf of St. Lawrence ecoregion).

Emma Perry on Conway Sandhills, PEI (Photo courtesy Emma Perry)

Perry chose four study sites around the island, two of which were located on NCC properties. Sadly, she found no tardigrades on NCC nature reserves, but did manage to find some at the other two sites, meaning PEI has its first recorded marine tardigrades. She is coming back to PEI next summer, and now that we have an idea of what kind of sediment they prefer, we are going to sample NCC nature reserves that have more tardigrade-friendly habitats. Although this is research that Perry is doing on largely on her own time and interest, she hopes to have the results published in 2018.

It is worth noting that even though she didn’t find tardigrades on NCC nature reserves, she found a whole bunch of other critters. Perry was kind enough to deliver a presentation to NCC, revealing the results of the aquatic invertebrates she found living in PEI’s intertidal zone. These tiny animals survive by eating the bacteria and tiny algae that also live within the intertidal zone. Through their digestive process, they break down and re-introduce nutrients back into the local marine benthic foodweb (Oecologia January 1978, Volume 33, Issue 1, pp 55–69).

Marine mite (Photo by Emma Perry)

Tardigrades, like most microscopic creatures, are not well studied or researched yet, and there is still much to learn about where they live and the true extent of their capabilities for survival. Are they found all over the world, adapted to every single climate and ecosystem? Are there limitations to their survival strategies? How will climate change impact their survival? How will learning more about tardigrades impact human lives? These are the sorts of questions that demonstrate just how much more we have to learn about the mysterious and beautiful order that evolved on planet Earth.

NCC has a goal to save ecologically sensitive landscapes, both for their inherent value and as the homes of plants and animals — not just for moose and piping plovers, but for the microscopic creatures, the micro-habitats and the biodiversity that we may never see or even discover.

This blog was written by Julie Vasseur with the assistance of Emma Perry.