Bidding farewell to National Poetry Month with a nod to science-inspired poets

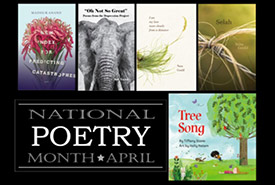

Composite of book covers (Photo by Science Borealis)

Poets need scientists. And some might argue that scientists need poets.

In the second semester of my master’s of fine arts program in writing (studying poetry and creative non-fiction), I began thinking about how a lack of basic scientific integrity in one’s creative work leads to failed metaphors.

The motivation for this reflection was a colleague’s poetry reading. One of his poems used mosquitoes in place of humans to say something about human romantic relationships. In his poem, the aggressive mosquito — the one who bites — was male. In nature, though, it is the female mosquito that bites and draws blood, and the male that sips flower nectar.

I thought about how significantly the message of his poem would change if he had reflected the nature of his characters accurately. By not doing so, I felt his metaphor failed.

But when I raised my belief that we poets should be scientifically accurate whenever possible, if for no other reason than to strengthen our metaphors, my peers dismissed my position with their argument for “poetic licence.”

Poetic licence to me suggests that the writer knows the truth but chooses not to reveal it because it doesn’t serve the larger message of their story or poem. Poetic licence does not, in my opinion, excuse ignorance, which I believe was the case in the male-biting-mosquito poem.

It has been many years since I walked out of that poetry reading contemplating the role of science in art and the artist’s responsibility to know their subject. I haven’t yet made peace with the poetic licence argument that seemed to suggest a metaphor based on imagination is stronger than, or at least equal to, one based on reality.

Because of my bias for factually accurate metaphors, I feel most at home in the space where science and art merge. As one way to celebrate this year’s National Poetry Month, I decided to seek out more science-inspired poetry. I would like to share some of the treasures I found this month as a way of highlighting what’s possible when people write about science with a poetic sensibility.

One poet-scientist who stands out for me, not only because of her lyrical voice but also her resourcefulness, is Madhur Anand. Madhur’s collection New Index for Predicting Catastrophes includes many poems composed entirely of language mined from scientific articles she has co-written. I’ve never encountered brilliance like hers. I am a lover of collage and a fan of “found poems,” so it shouldn’t surprise me that I feel so inspired and moved by her ability to discover and reveal the songs hidden within her own scientific research.

John Keats said, “Poetry should strike the reader as a wording of his own highest thoughts, and appear almost a remembrance.” Striking the reader as a wording of his own thoughts is exactly what Rob Taylor’s collection “Oh Not So Great”: Poems from the Depression Project achieves. These poems were written with the intention of offering doctors, “a doorway to empathy with patients who suffer from mental illness.”

I shared my life for several years with a man who suffers from depression. As soon as I began reading Rob’s work, my heart broke open. I felt like I was hearing my former partner’s most private thoughts. After discovering that Rob wrote these poems from transcripts taken from patients who shared their experiences of living with depression, my experience in reading them made perfect sense.

Nora Gould’s work also touched me deeply. Nora is a rancher and trained veterinarian who makes “absence” tangible — in life, attention and her husband’s dementia. She does this with an ear for language and heartfelt honesty. Her latest collection is Selah. Her first collection is called I See My Love More Clearly from a Distance.

Even though I am 43 years old, I’ve never outgrown my love of children’s books, especially those with a dash of whimsy and/or rhyme. Tiffany Stone writes for children, and one of her books, Tree Song, educates young people about the life cycle of trees. When I found it, I couldn’t help but put another book of hers, Rainbow Shoes, on my wish list.

As another way of diving into science-inspired poetry, I began substituting hashtags for afternoon coffee. Just as my 3 p.m. brain-lull started kicking in, I popped over to Twitter and fished for poems with #scipo #sciku #sciencehaiku #scipoetry and #scirap. I couldn’t have predicted the range of subjects or seriousness with which some scientists write haiku. Or rap.

The last treasure I would like to share is a link to a science-poetry-related celebration you can watch online, called Universe in Verse. This year marked the second annual gathering held in New York City. Roseanne Cash, one of the readers for the 2017 celebration, brought me to tears with her personal story and her reading of Adrienne Rich’s poem “Power,” a tribute to Marie Curie. (Fans of Cheryl Strayed’s book, Wild, will also find this poem familiar and moving.)

Anne Carson writes, “If prose is a house, poetry is a man on fire running quite fast through it.” Here’s hoping that my brief run through the house of science and song offers you a space to explore this unique genre, or maybe even the inspiration to write a poem of your own.

This article was written by Lené Gary, general science editor at Science Borealis, and originally appeared on their blog.