Collaborating with Indigenous communities for land conservation

Learning the Land brings educational projects and initiatives to schools and communities on Treaty 4 lands. (Photo by NCC)

Five years ago, in her work as the director of conservation for the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s (NCC’s) Saskatchewan Region, Jennifer McKillop had conversations with the Treaty Four Educational Alliance (T4EA) in order to start a relationship and get NCC further involved in working with Indigenous communities. Out of these conversations, Learning the Land was born.

Learning the Land brings educational projects and initiatives to schools and communities on Treaty 4 lands, in collaboration between the T4EA and NCC. The program aims to teach students about native prairie conservation and species at risk through a combination of western science and Indigenous Traditional Knowledge.

Jennifer sees partnerships with Indigenous communities in Saskatchewan as a vital part of NCC’s work as a land conservation organization. Today, she is the regional vice-president of the Region and strives to ensure that consulting and collaborating with Indigenous groups becomes a routine part of our conservation work.

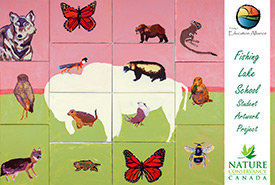

Species at risk mural that students from the Fishing Lake First Nation 89 School created with Cree artist Michael Lonechild. (Photo by NCC)

On my first day at NCC, the first thing I saw when I walked into the Saskatchewan Region’s conference room was a species at risk mural that students from the Fishing Lake First Nation 89 School created with Cree artist Michael Lonechild, as part of a Learning the Land workshop.

In the past five years, Learning the Land has developed many projects, such as creating a curriculum that combines science and Traditional Knowledge, bringing species at risk workshops to communities and helping Indigenous communities map traditionally important areas using equipment such as drones, iPads and GPS units.

Related content

Learning the Land’s most recent project was giving T4EA-affiliated schools the opportunity to create outdoor learning spaces in their communities. To supplement these spaces, a supply of resources was provided, such as field guides to help identity plants and wildlife, water- and soil-testing kits, snowshoes and materials to create molds of wildlife tracks. The community at Kawacatoose First Nation built an outdoor theatre and presentation space and created a garden plot.

The Asiniw-Kisik Education Campus on Kawacatoose First Nation built an outdoor theatre and presentation space and created a garden plot. (Photo by NCC)

In June, I drove out to Kawacatoose First Nation with Kayla Burak, engagement manager for NCC’s Saskatchewan Region and Learning the Land representative, to see the outdoor learning space and celebrate its completion.

We spent the day with students and staff from Asiniw-Kisik and T4EA, using the new outdoor structure and practising land-based learning activities centred around traditional Cree knowledge and practices.

With summer vacation less than a week away, energy levels were high. The students’ favourite activity was a traditional North American Indigenous sport called double ball. T4EA’s student engagement facilitator, Lamarr Oksasikewiyin, lived up to his job description and led the high-spirited game.

The students’ favourite activity was a traditional North American Indigenous sport called double ball. (Photo by NCC)

On the surface, double ball is similar to lacrosse, but instead of a ball, there are two sand-filled balloons wrapped in hide. And instead of a lacrosse stick, a stripped wooden stick is used. The “double ball” used in the game was originally buffalo testicles. Lamarr told the students that because of the sacred position of the buffalo in many prairie Indigenous communities, they could only touch the double ball with the stick and not their hands.

Earlier in the day, one Asiniw-Kisik teacher taught his students Cree words for animals. He told them the Nehiyawewin (Plains Cree) word for owl is oho, pronounced “hoho.” As he held up a silicone imprint of an owl’s foot, he explained that the name comes from the sound an owl makes, “ho-ho-hoho.”

Harold Littletent, cultural advisor with the Touchwood Agency Tribal Council, talked to students about sacred objects, such as eagle feathers and ceremonial drums. (Photo by NCC)

Sitting in the shelter of another part of the structure, Harold Littletent, cultural advisor with the Touchwood Agency Tribal Council, talked to students about sacred objects, such as eagle feathers and ceremonial drums. He cautioned the students to remember to leave an offering of tobacco any time they pick ceremonial plants like sweetgrass.

At the end of our day at Kawacatoose, as we beat the rain and drove back to our Regina office, I thought about the future of conservation. I thought about the very clear, common vision between the work that conservation organizations do and the work that many Indigenous communities are doing to stengthen their Traditional Knowledge: taking better care of this land and investing in our youth as the future caretakers of this land.

Projects like Learning the Land are an essential part of doing effective conservation work in Canada. There can be no meaningful conservation of this land without acknowledgement of and collaboration with the communities whose ancestors conserved this land for thousands of years.

To learn more about the work that NCC’s Saskatchewan Region is doing with Learning the Land, visit learningtheland.ca.

The Conservation Internship Program is funded in part by the Government of Canada's Summer Work Experience program.