Conservation, the cowboy way

Waldron shareholders at the King Ranch (Photo by Karol Dabbs)

I was raised within a ranching family. I grew up in southern Alberta, fixing fences in the summer heat and feeding livestock in the winter. I’ve been riding horses since I was three years old, was a member of my local 4-H club and I read the Western Producer [agricultural] newspaper every week. I can relate to landowners who deal with trespassers or to hunters asking landowners for permission to hunt in the fall. And I understand the work that goes into maintaining a piece of private land or running a working ranch.

For the last two summers, I worked with the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) as a conservation intern. In many ways, the lessons I learned through ranching related directly to my experience working with the conservation organization.

I believe in the conservation and sustainability of our private lands in Canada. If we — the ranching and environmental communities — plan on being around in the next century, we have to manage our lands in perpetuity by integrating sustainable ranching or land-use practices.

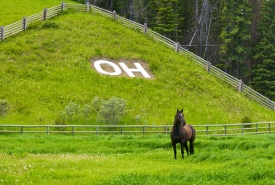

OH Ranch, AB (Photo by Karol Dabbs)

Practices such as sustainable grazing techniques, efficient water usage, wildlife friendly fencing and weed control are all part of the larger picture. The constant battle between making a living off the land and conservation always comes down to money. With the continuous inflation of ranch operation costs comes the need to increase livestock production, adding pressure to a forever-shrinking landscape — a balance even the best cowboy conservationist struggles with.

You can lead a horse to conservation

It’s no secret that ranchers love their land, and with that love comes the sacrifice of investing as much personal time and effort into it as possible. Many times I have used the same tools for conservation tasks at work with NCC as I do ranching at home, because I am doing a similar (if not the same) job.

Reclamation of Fleming Ranch, AB (Photo by NCC)

These tools range from fencing pliers to trailers and anywhere in between. However, the greatest tool I use on my ranch is my horse.

A major part of conservation is helping reduce the physical impact of humans on the land. While working for NCC, I reduced my impact by using a horse instead of an ATV. There isn’t much an ATV can do that my horse can’t. First of all, you can go almost anywhere on a horse, and many places that you can’t with a machine. You don’t have to cut trees or clear paths; you just walk around obstacles a different way. I may not be able to race across flat terrain at 80 kilometres per hour, but I can cross just about any creek or small river that southern Alberta has to offer, at almost any point, with minimal impact.

I have fixed fences, cleared treed-in fence lines and I have even packed out on a horse garbage bags full of invasive weeds. While working on non-NCC land with horses, I have found that landowners respond very positively when I pull into their yard with a horse trailer. They tend to appreciate the low impact of horse hooves over ATV tracks weaving through their property.

There have even been a few landowners who have joined me on horseback while, as a conservation intern with NCC, we monitored a conservation agreement property, which is extremely helpful for us as well as for the relationship that we hold with those individuals.

Waldron shareholders at King Ranch, AB (Photo by Karol Dabbs)

It’s a great opportunity to get an in-depth look at the property as well as its history, and also a perfect time to hold conversations about future projects or ideas the landowner has. I truly believe that saddle horses are one of the most overlooked and underutilized tools of conservation today.

Bridging the relationship between the cowboy and the conservationist

After spending much time in the field and around the area of NCC properties, I have had to explain my role with NCC to multiple people that I meet. I suppose we have company decals on the field truck for a reason, right? I usually explain who NCC is and what we do as an organization in the area, as well as how I fit into that picture. However, I have recently thought of a simplified explanation: NCC bridges the gap between the science behind private land conservation and the private landowners who have years of on-the-ground land management experience. Both groups have values that can be shared with each other to become better land managers and positively influence the ecological value of the landscape.

Great things can happen when mutual respect is had between the two parties, and both are willing to help each other for a common goal: conserving a landscape to its greatest beauty and productivity for generations to come. The key to this bridge is the personal relationship between the cowboy and the conservationist.