Discoveries in little-known fungi: Adventures in looking at lichens

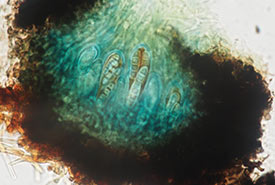

Opegrapha parmeliiperda, cross section of one fruiting body showing four-celled spores developing inside spore sacs; blue colour result of treatment with potassium hydroxide followed by Lugol’s iodine solution. (Photo courtesy of Kendra Driscoll)

I used to think that scientists understood the basics about most living things on Earth, that new species were all discovered long ago by people like Linnaeus and Darwin. Maybe you could find new species in the most remote corners of the planet, but we know all about the species in inhabited parts of North America, right?

Wrong! It turns out that documenting all the species in any ecosystem is an enormous task that we may, literally, never finish. New discoveries are not unusual, even among well-studied groups. Some organisms have received so little attention that we know practically nothing about them in some regions.

I started studying lichens under Stephen Clayden at the New Brunswick Museum (NBM) in 2006 and immediately fell in love with them. They are symbiotic organisms, combining a fungus with at least one alga or cyanobacterium that can harness the power of the sun to make food. They come in many different shapes and colours and live everywhere from balmy jungles to bare Antarctic rocks. With relatively few people studying lichens and many species that are small, rare or difficult to identify, they’re often overlooked. Basically, there’s lots left to discover. My first couple of years working with them felt like a treasure hunt.

Distribution map showing lichenicolous fungi in genus Opegrapha recently reported from New Brunswick. All were first records for the province. Opegrapha lamyi was reported for the first time in Canada. Opegrapha inconspicua and Opegrapha parmeliiperda were described as new to science. Click to enlarge.

Soon I learned that many lichens also play host to fungal parasites known as lichenicolous fungi. These nifty little fungi are also quite variable in appearance and in how they live. Some kill their lichen host, others are pretty benign. Some are closely related to lichens, others are related to mushrooms. Some are so specialized that they can only live on a single host species. If lichens were under-reported, these fungi had barely been studied at all!

In 2007, there were only seven species of lichenicolous fungi reported from New Brunswick in the scientific literature, and we knew the diversity must be much higher. By 2011, we had assembled an international team of researchers willing to contribute their records, with the goal of producing a checklist and identification resource for Atlantic Canada. It’s an ambitious project, with 228 species documented so far for Atlantic Canada, including 161 from New Brunswick (a 22-fold increase over 14 years)!

The checklist is still a work in progress, with more species added every year. In the meantime, several interesting discoveries have been reported, including new species and species never before reported from North America.

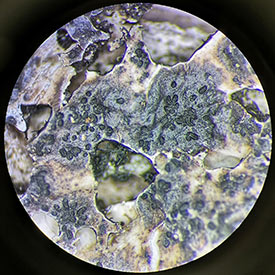

Healthy shield lichen (Photo courtesy of Kendra Driscoll)

The most recent stride forward was a paper published earlier this year in The Bryologist. Stephen and I teamed up with Damien Ertz of Meise Botanic Garden in Belgium to report five lichenicolous fungi in the genus Opegrapha for the first time in New Brunswick, including two species new to science! These new species are currently known only from NB. The lichens they infect are widespread across the northern hemisphere, so it is likely they may turn up on in other parts of North America or on another continent entirely! But there might be other factors influencing their distributions. Opegrapha inconspicua — so named for its inconspicuous appearance owing to its small size — turned up on a rock-encrusting lichen at a single site in Jacquet River Gorge Protected Natural Area during NBM’s annual BiotaNB biodiversity survey effort.

Opegrapha parmeliiperda, new species described growing on shield lichens in swamp-forests containing eastern white cedar in New Brunswick. (Photo courtesy of Kendra Driscoll)

Opegrapha parmeliiperda— whose name means “destroyer of Parmelia”— has been found in four sites around the province, infecting and perhaps eventually killing grey lichens in the genus Parmelia, often called shield lichens. The host lichens for this second species are common and widespread, but the fungus so far seems restricted to swamp forests with eastern white cedar, a habitat exceptionally high in lichen diversity.

Surely knowing the species around us is a fundamental step toward understanding ecosystems. As we attempt to navigate the global environmental crisis, I believe that the need for biodiversity research has never been so urgent. We have so much to learn, and so much to lose.