Not my story: What it means to be bison people

Views from Buffalo Treaty Signing Ceremony at Prince Albert National Park (Photo by Anthony Johnson)

I really like telling stories about the crazy things that happen to me at work. I also like telling other people’s crazy stories that I haven’t even witnessed. Ask me about the adventures of my buddy Tyler. He gets up to some interesting things over in Dawson Creek, British Columbia, and you wouldn’t believe the things I have him saying in my retellings. Whatever gets me the attention I crave, I guess.

But maybe not everything has to be crazy and hilarious to be told. And maybe not everything has to be directly about the birds we identify and the grasses we love. How about a story — someone else’s story — about bison, grass and people? It is not my story, but it's definitely a Saskatchewan story about an aspect of conservation that doesn’t get mentioned too often.

Buffalo treaties (Photo by Anthony Johnson)

As a member of the Prince Albert Model Forest, the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s (NCC’s) Saskatchewan Region was invited to attend a Buffalo Treaty Signing Ceremony hosted by the Mistawasis First Nation. Anthony Johnson, Mistawasis First Nations manager of special projects, and Sarah Schmidt, general manager of Prince Albert Model Forest, worked really hard along with many other people and groups to host an event that celebrated the importance of bison to the people of Saskatchewan.

Dancer from Muskeg Lake First Nation (Photo by Anthony Johnson)

The event was held at a cultural site in Prince Albert National Park, in a relatively open spot in the forest. The site has widely spaced towering aspen. There is an outer ring of imposing white spruce and jack pine that I kept hoping a bison would poke its head out of. But the bison we were all there to celebrate and conserve were not the remembered herds of our past or some idea of a herd on the other side of a fence. It’s a living, breathing, free-roaming herd of plains bison translocated from Elk Island National Park, Alberta, to Montreal Lake, Saskatchewan, in the 1960s to provide meat for the First Nations people living in the area. Almost immediately, the herd relocated themselves 100 kilometres to the southwest corner of Prince Albert National Park, where they have been living, pawing, grazing and generally doing bison-related things ever since. And I guess I should add interacting with humans, because that is something people and bison have been doing for a long time.

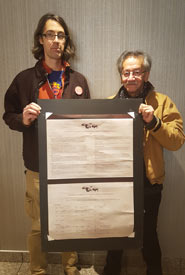

Matthew Braun and Anthony Johnson holding the signed treaty (Photo by NCC)

That is really where this story stops being my story to tell. I mean, I interact with bison. I eat them, help with Old Man on His Back Bison Ranch as best as I can, watch them from the other side of the fence, I help manage them, but that is not the same thing as being a bison person, which is something this treaty was trying to accomplish. So what does it mean to be a bison person? Well, I’ve heard Anthony tell the story and maybe someday you will hear him or one of the people he inspires tell their story too. He and the people he gathered to that site to celebrate the importance of living with bison have stories to tell and stories to live. I am not a bison person because it isn’t in my DNA or intertwined in my family’s story of living and dying in this province, but maybe it will be part of my story or at least my kids’ stories if the work that Anthony and Sarah and so many others have started is successful.

I hope to have a better understanding as I continue to work and live here, but what I gathered about being bison people from my relationship with Anthony and Sarah so far is that to conserve your culture, your economy and your environment you have to thoroughly intertwine all of them. Part of that process is getting together in a grassy, open forest to dance in the grass, sing songs, eat some bison chili and sign a treaty that declares that together we can accomplish restoration.