So you’ve acquired a property. Now what? (part one)

Is this what you think of when you hear conservation biology? ( Photo by Mike Dembeck)

New things are exciting. In my first few years as the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s coordinator, conservation biology for eastern Ontario, I couldn’t figure out why my favourite property kept changing. At first, it was the Emma Young property in the Loughborough Wilderness Block (and with views like this, can you blame me?).

Wetland on the Allum property, ON (Photo by NCC)

But the next year it was the Jack Hunter Allum property that caught my attention.

Benson Lake wetland in the Frontenac Arch, ON (Photo by NCC)

And now in 2020, my favourite is Benson Lake in the Frontenac Arch, eastern Ontario.

I couldn’t figure out why my favourite property was changing so often, until I realized I was falling in love with every new NCC property that I was entrusted to oversee in eastern Ontario.

When NCC acquires a new property, whether through purchase, donation or conservation agreement, my first task as head of the stewardship team is to prepare a baseline inventory. A baseline inventory is a detailed report on the plants, animals and human features on the property. This inventory is then used to develop a property management plan, which outlines the targets (what we want to protect), the threats (what could negatively impact the targets) and the concrete actions needed to make sure these goals stay on track.

As a science-based organization, we pride ourselves on getting the answers before making decisions, and when we have questions about new properties, we answer them using a baseline inventory.

Here are the steps to writing a baseline inventory.

Step 1: Plan, plan, plan

If I had my way, I could justify spending all summer exploring new properties to find every last leaf, insect and fence. But since I have over 10,000 hectares (25,000 acres) to manage, that’s not reasonable. Before I even step foot onto a property, there are a lot of behind-the-scenes steps happening in the office to streamline the baseline inventory process.

First, I need to know where a property is. Is it close to an existing NCC property? Can I access it by car, or is it better to travel by boat? How far away from the office is it? Then I bring out the maps.

Initial sketch of features (Photo by NCC)

Our GIS department provides a blank map showing a satellite image and the property boundary, which we use to delineate possible features. Something we are trained to do is look at shapes on the image, and make educated guesses of what those features are before we get a chance to see them in person. Is there a river running through the property? Does the forest on the east side of the property look different from the west? Are there any buildings or large features? What is that strange, dark mass in the centre? (I’ve learned from experience that it’s usually a wetland.)

Initial sketch of features (Photo by NCC)

As I explained in a previous blog, I’m not an artist, but the map I create in the office doesn’t have to look pretty. It acts as a first guess of how many major vegetation communities we might have on site, and highlights any features that should be visited on the ground.

Step 2: Ground truthing

It’s a labour-intensive process to do the field work for a baseline inventory. Without a plan, the days can feel quite chaotic. I like to start by walking around the property to get a “feel” for it. Using a compass, my hand-drawn map and a GPS unit, I navigate to the highlighted spots on the map to see what’s happening on the ground. This is called ground truthing, as we’re checking if what we thought was on the ground is true.

I know NCC’s properties in eastern Ontario like the back of my hand. I know where to cross the stream on the Freeman property to avoid getting my boots wet, and where to eat lunch on the Goodfellow property if I want a beautiful view. The exciting part about a baseline inventory is figuring out the little quirks that make a property unique.

I’m looking for many thing while doing field work for a baseline inventory. Step two is split into multiple parts because, realistically, I’m never just doing one thing at a time. While I’m gathering information about the vegetation communities, I’m also looking at species and keeping an eye out for any hazards.

Step 2a: Vegetation community classification

Ecological Land Classification (ELC) is a standard system of categorizing an ecosystem based on many factors, including the vegetation, soil, geology and topography. When you go through the process of ELC, you get a code of letters and numbers that tells you a lot of information about a community.

For example, code THDM2-7 means Prickly Ash Deciduous Shrub Thicket, so if I’m looking for an easy way to navigate around a property, I probably shouldn’t go there (It’s called prickly ash for a reason). FODM5-2, the Dry-Fresh Sugar Maple-Beech Deciduous Forest is probably a better option.

It would be impractical for us to try and identify every single plant we come across during a baseline inventory, but knowing the ELC code gives us clues about what species we can expect to find there.

On site, when we get to a distinct ecosystem, we work from the top of the canopy down to record the species of trees, shrubs, vascular plants, grasses, mosses, lichens and underwater vegetation. We keep a running list of species and note their abundance. Is the area dominated by one species, or is it an even mix? We also consider the soil. Are we in a saturated area (like a swamp), or is the soil dry? We look at the composition of the space. What percentage of the area is vegetation? Rock? Woody debris? Exposed soil? Water? How much canopy closure do we have? 20 per cent? 50 per cent? My job is to piece these clues together to paint a picture of the landscape.

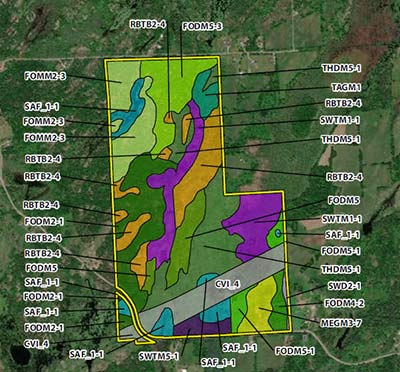

An example of a map with vegetation communities labelled on a property. (Map by NCC)

Some ecosystems are rare, and if there is one on a property, I want to know about it! Sometimes we get lucky and the communities on the ground match up with what I originally drew, but that’s not always the case (sometimes that dark blob is actually just a shadow). That’s why it’s vital to ground truth.

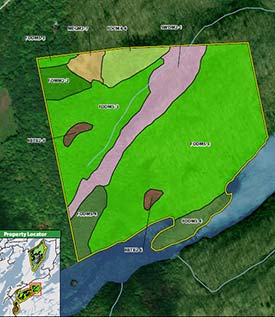

Another example of a map but with less vegetation communities. (Map by NCC)

Somehow the GIS department takes my poorly coloured maps and hand-written notes and turns them into something beautiful and usable. Tune into part two of this blog to see how we collect information about species, anthropogenic (human-made) items and write the baseline inventory.