Making friends with the solitary bees

Blue orchard bee (Photo by Robert Engelhardt)

When you think of bees, your mind probably goes to honey, hives and stingers. But what if I told you that there was a species of bee, native to the Saskatchewan prairies, that didn’t make honey, live in a hive or (usually) sting?

Mason bees are solitary nesters who don’t bother with wax or hives and instead lay their eggs in hollow plant stalks corked with mud. However, even if these bees don’t give us candles or anything to spread on toast, they are still an important part of our ecosystem as expert pollinators. Pollinators are executive assistants in the work that the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) does to preserve and restore native grassland in the Prairies.

Bee hotels (Photo by NCC)

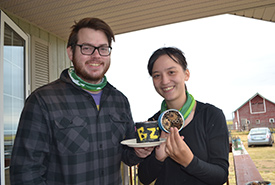

This August, my co-workers spent a camp-out weekend at NCC's Old Man on His Back Prairie and Heritage Conservation Area in southern Saskatchewan. While they were there, they showed 40 Conservation Volunteers how to make simple structures, called bee hotels, from cans, miscellaneous natural materials and hollow bamboo stalks. As an alternative to bamboo, you can find cardboard tubes sold online that are made specifically for use in bee hotels, which are what my co-workers used that weekend. These hotels create habitat for solitary bees like mason bees to nest and lay their eggs in.

Related blog posts

My family has kept honeybees on our out-of-town property on and off since I was a baby. (Photo courtesy of Maia Herriot/NCC staff)

I’m no stranger to bees. My family has kept honeybees on our out-of-town property on and off since I was a baby. I grew up knowing that if a wasp stings you, it’s not your fault, but if a honeybee stings you, it’s probably something you did. To me, the relationship between bees and humans always seemed mutually beneficial; we give them a safe home and, if we lull them into smoky sleep, they give us honey.

There is also a community around beekeeping and local honey production that seemed to me to mirror the interdependent, supportive community within a hive. That’s why when I learned about solitary, non-honey-producing bees for the first time this summer, it shook my perception about our relationship with bees in general. My understanding shifted after hearing my co-workers talk about creating the bee hotels and the environmental benefits of focused pollinators like mason bees.

Hearing my co-workers talk about creating the bee hotels and the environmental benefits of focused pollinators like mason bees, my understanding shifted. (Photo by NCC)

Another layer of our relationship with bees is how our ways of life are more clearly interconnected. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “The global decline in bee populations poses a serious threat to a wide variety of plants critical to human well-being and livelihoods, and countries should do more to safeguard our key allies in the fight against hunger and malnutrition.” Basically, we need to do more for the bees.

Beekeeping gives us the ability to view the inner workings of a bee hive and feel as though we are in some way a part of it. But there’s an equally fulfilling feeling when we do something for the bees without asking for anything in return. If domesticated honey bees have something to teach us with their co-dependency, wild solitary bees have something to teach us with their independence.

There’s a fulfilling feeling when we do something for the bees without asking for anything in return. (Photo by NCC)

Even as we share the Earth with them and our fates become intertwined, bees seem to live in a different plain; a smaller, simpler one made up of the powdery centres of brightly coloured flowers and the safety of a hole or a hive. They pollinate for their own sake, unaware of how vital their actions are to our ecosystem and food production.

As much as I like honey and the smell of wax candles, there’s something beautiful about doing someone a favour when you know they will never try to give you anything in return — a friend who will shack up in a bamboo stem you bought for them without ever thanking you. That way, you don’t do it for the thanks. You do it for the grasslands and the future and the bees themselves.

The Conservation Internship Program is funded in part by the Government of Canada's Summer Work Experience program.