The Traills at Rice Lake

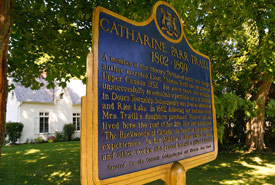

A view of the former home of Canadian author Catharine Parr Traill taken on Friday, September 19, 2014 on Smith Rd. in Lakefield. (Photo by Clifford Skarstedt/Peterborough Examiner/QMI Agency)

Ontarians usually associate Catharine Parr Traill with her book, The Backwoods of Canada. Those backwoods were located near Lakefield where she and her husband Thomas first pioneered on land just to the south of what is now Lakefield College School.

Parr Traill then lived her final four decades on Smith St. in Lakefield, in a house built for her by her brother, Sam Strickland, and friends.

But from 1846 to 1858 the Traill family lived on the Rice Lake Plains in three different homes — Wolf Tower, Mt. Ararat (so named by Catharine herself) and Oaklands, the farm they bought in 1849 and where the family lived until a late-night fire destroyed the house and most of their belongings. That fire was the last straw for Thomas, who died a broken man a year later.

I reacquainted myself with the Traills at Rice Lake upon receiving an invitation from the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) to talk about her work there as an amateur botanist. I was asked to talk about Traill's descriptions and perceptions of the Rice Lake Plains because they constitute an important historical record during the 1840s-1850s, just at the time when white settlers were beginning to buy up and settle the land around Rice Lake.

NCC has been gifted or has purchased several properties in the Rice Lake area and, among other projects, staff are carefully restoring an important ecological system that scientists now identify as tall grass prairie and oak savanah. Such grasslands once made up large parts of early Ontario, but in the Rice Lake area there are patches of "prairie" that remain much as they once were. Unfortunately, various invasive species have taken root in this habitat over time.

Catherine Parr Traill

The Traills came to Rice Lake first as visitors (for a year at Wolf Tower), then as renters (at Mt. Ararat) and finally as land owners at Oaklands. These place names persist to this day in part because Catharine wrote so evocatively about them. Her time at Rice Lake was a special pleasure for her as it followed several difficult years of poor health, the deaths of two children and near bankruptcy, all while living in the Peterborough area. At Rice Lake she found the air and climate wonderfully reinvigorating. Here, she was better able to teach her six children about the natural world and to make time for her own writing.

In fact, while living at Rice Lake she published three books and numerous articles, notably Canadian Crusoes: A Tale of the Rice Lake Plains (1852) (also published under the title Lost in the Backwoods), The Canadian's Settlers Guide (1855) and a children's book called Lady Mary and her Nurse (1856) (also published as Afar in the Forest). In these books and in later publications like Studies in Plant Life in Canada (1884), Parr Traill celebrated the plant, shrubs and grasses of the Rice Lake Plains. She treasured her rambles over the hills and valleys of the plains in search of species and enjoyed the opportunity to study and document them. So strong was her maternal affection for plants that she saw herself as their floral godmother. Botany has seldom received so humane and caring a study.

The Nature Conservancy of Canada has identified the Rice Lake prairie and savannah as one of the world's rarest and most endangered ecosystems. Today on a national basis only one percent of the original prairie remains; however, the Rice Lake Plains include excellent quality prairie remnants that can be actively restored by means of prescribed burns and careful planting.

Having been gifted an excellent tract of such prairie by Hazel Bird, a local woman duly famous for her work in bringing back the endangered eastern blue bird, NCC has been implementing restoration programs designed to revitalize the mix of forest lands, savannah and grasslands at the Hazel Bird Nature Preserve. For instance, they have slowly been bringing back the rare black oak and various plants native while trying to eliminate invasive species such as Scotch pine.

As a speaker in NCC's series, Nature Talks, I called attention to Parr Traill's descriptions of the plains in the 1850s, noting her interest in the geological development of the deep ravines above Gore's Landing and what she called the upper and lower "race courses" that make up the fertile plains above the southwest side of Rice Lake.

I read a few of her descriptions of the dominant floral species of the area; these she liked to organize by the season. As well, I noted her interest in the wild rice harvested yearly by the native peoples of Alderville and Hiawatha, and her fascination with the burns that over the years have kept the prairie and savannahs close to their original state. Parr Traill was, I noted, a conservationist at heart.

She knew that she and her family were part of the march of civilization westward and that nature would inevitably suffer many losses as a result of the mass intrusion of settlers. However, as a pre-Darwinian botanist, she believed in God's divine plan and handiwork; "this lovely plain," she believed, had been "planted by the hand of taste." It would continue to endure under the Creator's watchful eye.

Since prescribed burns are one of the NCC's major strategies for preservation and restoration, I was particularly interested in Traill's understanding of them. She certainly knew that such fires were often credited to the native peoples as their means of abetting deer hunting on the Plains. But, in fact, Catharine never saw a burn herself; still, she readily gauged their value as a conservational tool. Thus, she has one of her young adventurers of the late 18th century observe in Canadian Crusoes.

The fire passes so rapidly over that it does not destroy many of the forest trees, only the dead ones are destroyed; and that, you know, leaves more space for the living ones to grow and thrive. I have seen, the year after a fire has run in the bush, a new and fresh set of plants spring up and even some that looked withered recover. The earth is renewed and manured by the ashes, and it is not so great a misfortune as it first appears.

Catharine Parr Traill might have been describing an NCC burn at the Hazel Bird Nature Preserve. She was a careful observer who knew the value of (controlled) burns and understood their worth in revitalizing the land and the flora she loved.

This article was first published in the Peterborough Examiner and is reposted with permission on Land Lines.

Michael Peterman is professor emeritus of English literature at Trent University. Email him at mpeterman@trent.ca.