What is Alice Munro reading these days? My review of The Once and Future Great Lakes

Waves crash on the northwestern Lake Superior Coast, Ontario (Photo by John Anderson)

The Great Lakes come by their name honestly — at 244,106 square kilometres, spanning across eight states and one province, lapping the shores of approximately 35,000 islands, these five lakes have shaped the natural and cultural history of many parts of North America.

These waters have also played a defining role in my personal history. As a child growing up in Meaford, Ontario on the shores of Georgian Bay and Lake Huron, the waters of the Great Lakes were never far away. Our summers were spent in a cottage on the mighty St. Lawrence near Brockville, where you could daily see the shipping traffic moving freight between the Great Lakes and overseas destinations.

Lake Superior coastal wetland, Ontario (Photo by NCC)

I live in a major city on the shores of Lake Ontario. I have often visited the shores of Lake Erie to witness the spring and fall migration of thousands of birds and waterfowl. And I have dipped my paddle into the waters of the French and Mattawa Rivers and on occasion have braved a swim in Lake Superior’s chilly but clear waters.

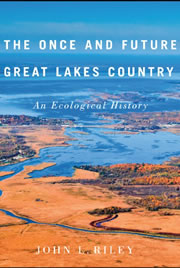

Now, a new book by Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) Senior Science Officer John Riley explores the long and varied history of the Great Lakes, and their cultural and historical importance. Published by McGill-Queen’s University Press, The Once and Future Great Lakes Country presents a detailed accounting of the geologic, natural and human history of the Great Lakes Region — an area that, according to Riley, “now supports a population of more than forty-five million and a shared annual economy of more than $1 trillion. It is a place that is open to the continent, and now to the world, more of a crossroads than anything separate or insular.”

A Once and Future Great Lakes Country (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2013)

We sometimes forget the ebb and flow of nature and the role that geography plays. Riley's book is a good reminder.

The second part of the book, “Voices of Nature Past,” examines “the trauma that occurred as the result of our assumption of the region’s lands and waters, fish and wildlife, and forests and prairies.” The stories are told through the voices of visitors, first peoples, explorers and surveyors, “who left us first-hand accounts of a series of profound ecological transformations.”

The third section, “Nature’s Prospect,” asks how Great Lakes country has changed since its early settlement in the 18th century. Riley puts the impact of our industrial world on the lakes into perspective. He also provides a longer-term perspective on the problems of today, while cautioning us to think more carefully about the impact of our actions on the future.

Yet despite centuries of human use and land management, Riley’s assessment of the Great Lakes Region in its present state is cautiously optimistic. He ends on a hopeful note, writing:

Shore of the Middle Point Woods property, Pelee Island, Ontario (Photo by Sam Brinker, OMNR)

“On balance, the evidence to date across Great Lakes country suggests that we have reinvested well. In comparison with a century ago, there is now more forest cover, cleaner water, recovering native biota, and an improved quality of life. It is nothing like the original ‘paradise,’ but there are many new and ambitious environmental policies and pursuits, restoring some of the region’s ecological integrity even while we intensify development in some parts of it.”

A Once and Future Great Lakes will be relevant to anyone with an interest in natural history. We at NCC were recently happy to learn that we are in good company — in an online chat with Margaret Atwood, when asked what she was reading now, Alice Munro enthusiastically stated that she was reading Riley’s book, and recommended it to others.