Ecosystem restoration

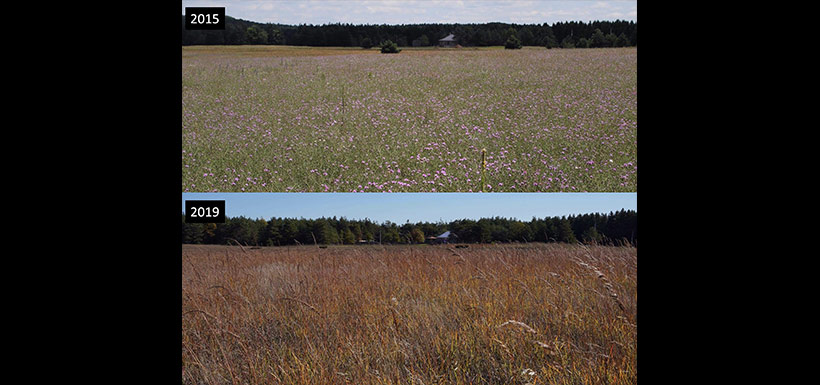

Once a farm field, now a new wetland (Photo by NCC)

Viable ecosystems are vital to both the health of humans and the planet. As a result, scientists are increasingly calling for us to rethink our relationship with nature. Viable ecosystems are not just the plants and animals that we see, but also what lies beneath our feet: the soil and microbes. From the food on our tables to our mental health and well-being, nature provides us with a myriad of services that are both essential and largely undervalued. Nature is also one of the most powerful solutions to today's dual crises of climate change and biodiversity loss. Yet humans have modified 77 per cent of terrestrial ecosystems (excluding Antarctica) and 87 per cent of oceans globally.

The value of restoring habitats

Viable ecosystems have many benefits and perform essential services that we may not even notice:

- Wetlands filter water.

- Healthy habitats remove air pollution.

- Wetlands and forests can hold back floodwaters.

- Forests, grasslands and peatlands sequester carbon.

- Nature provides food security and is a source of livelihood for many people.

The United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021–2030) is a call for the world to “prevent, halt and reverse the degradation of ecosystems on every continent and in every ocean.” Canada is no exception to this call to action, being home to 25 per cent of the world’s wetlands and the remaining 0.1 per cent of tall grass prairie globally. Ecosystem restoration in our country will play a huge role in ending the biodiversity crisis, meeting global climate goals and improving human well-being.

At the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC), we conserve biodiversity by acquiring and partnering with communities to protect important natural areas. But because of habitat degradation, NCC must often restore ecosystems in the natural areas where we work. Ecosystem restoration can include the always popular tree planting, but there are many more activities that are essential to restoring degraded ecosystems.

Restoration can be time and labour-intensive, and the landscape may take years to be restored to a goal-state. With support from partners, organizations, governments and communities, NCC is focused on helping to restore habitats across Canada. Learn about some of these projects on this interactive map supported by TD Bank Group.

Examples of restoration activities

- Planting native trees/wildflowers/grasses

- Conducting prescribed burns

- Restoring agricultural lands into uplands/wetlands or forest to open grassland

- Restoring Ontario’s deep south on Pelee Island

- A customized pond for turtles and fish in Quebec

- Restoring an open landscape on Kootenay River Ranch, BC

- Reintroducing species

- Removing invasive species

- Removing dams for river connectivity

- Rehabilitating degraded shoreline

Expand each photo in this gallery to learn about the impact of restoration on these NCC properties:

Improving habitat connectivity

Strategically restoring habitats can increase connectivity between isolated protected areas, allowing the movement of animals and the dispersal of plants across the landscape. Restoring habitat along a wildlife corridor allows wide-ranging animals to move safely between habitats to reproduce, feed or find shelter. For example, the Chignecto Isthmus allows moose to move from New Brunswick, where their population numbers are healthy, to Nova Scotia, where they are endangered.

Rebuilding the environment

Prescribed burn at Cowichan Garry Oak Preserve (Photo by Pete Laing)

Another aspect of restoration is returning native species to the land, while eradicating non-native, invasive species. Canada is home to approximately 80,000 documented species, with just over 300 that are found nowhere else in the world. In most studies, animals prefer native plants — those that occur naturally in an area where they evolved. One study showed that, as a result of this preference, native plants supported more species than non-native plants. On the other hand, invasive species outcompete native species, altering natural habitats and, ultimately, reducing ecosystem function. Removing non-native invasive species is an essential component of rebuilding the natural environment.

Climate change adaptation

In restoring degraded habitats, we are not only protecting biodiversity, but creating more resilience to a changing climate. We are already seeing several impacts of climate change, including increasingly intense and frequent extreme weather events that result in flooding and drought, rising sea levels, increasing intensity of forest fires and a shift in species distributions. But in the face of a warming climate, restoring nature can help cool air during heatwaves, as trees provide shade and transpiration.

Comparing the temperatures to vegetation data recorded by NCC staff over the last 12 years. (Image by Jonas Hamberg)

As an ecosystem matures, its ability to absorb the sun’s heat improves and it becomes cooler (check out this thermal imagery on an NCC property in Norfolk County). Protecting fresh water and wetland habitats can ensure communities have a constant supply of clean water during droughts.

While peatlands account for only three per cent of global land area, they contain 25 per cent of global soil carbon. So, keeping them intact is crucial to ensuring they remain carbon sinks instead of carbon source

As species ranges shift due to climate change, our role is to ensure there are corridors and minimize impediment, and there are protected natural areas for migrated species.

Restoring…to what?

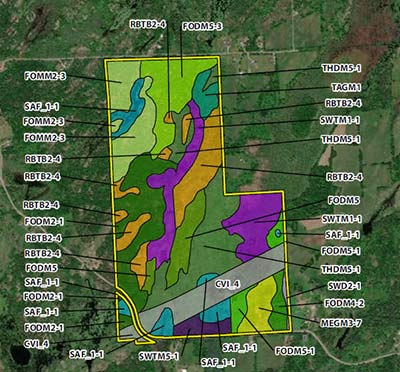

An example of a map with vegetation communities labelled on a property. (Map by NCC)

With land protection comes huge responsibility. Even ecosystems dominated by native plants can need restoring. In order to restore habitat, we need to know what it was like before degradation or altered state. Conservationists use many tools to help inform their work, such as aerial imagery, soil sampling, conducting baseline surveys, using a geographic information mapping system and historical documents.

However, it’s not always possible to know what an area looked like at a given point in time. And often, habitats have changed many times during the last 10,000 years as a result of natural changes or management by Indigenous Peoples. In many instances, conservationists approach restoration with questions that can guide their decisions, for example:

- How can we best support the specific species that are most in need of our help?

- How many contiguous hectares of what canopy cover or vegetation structure does the rarest bird in our region need?

- What host plants does this rare butterfly need to successfully lay eggs?

NCC uses traditional conservation methods and techniques, such as prescribed burning on grassland habitats across the country, to restore areas and promote the growth and return of native species. Click to enlarge this map of active NCC projects across the country that include restoration activities in their management plan. By working with Indigenous Peoples, NCC has been able to incorporate traditional ways of caring for the land. To learn more about how we’re working with Indigenous Peoples on the land, click here >