Episode One: The Last Five Miles

Grizzly bear, AB (Photo by Mike Gibeau)

This is the story about one of Alberta’s most distinctive landscapes. It is also about the people protecting it, who have managed to share the space with some of North America’s largest mammals, like the grizzly bear.

Take the quiz here

NCC on location: Waterton Park Front

Castbox | Podbean | Player FM | Stitcher | TuneIn

Transcript: The Last Five Miles

TIFFANY CASSIDY (HOST): This is the story of one of Alberta’s most distinctive landscapes, and the people who share it with nature.

LARRY SIMPSON: There's such a richness here and a spaciousness here.

JULIA PALMER: They're so magnificent those large animals.

CHARLIE RUSSELL: I wanted to understand these animals as they really were.

JULIA PALMER: We share this space.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: You’re listening to Nature Talks: the Nature Conservancy of Canada podcast. Fascinating stories about nature, why we need it in our lives, and the passionate Canadians helping to protect it.

I’m Tiffany Cassidy. This is episode one — The Last Five Miles.

(SOUND OF HUMANS WALKING ON GRASS)

TIFFANY CASSIDY: We’re heading down a grassy hill towards a river. This is Alberta’s Eastern Slopes — the point where rugged prairie runs smack into the Rocky Mountains. Off in the distance, Waterton Lakes National Park. On the horizon, snow-capped mountains that feel so close, you could reach out and touch them. At the edge of the river, a small herd of deer is drinking.

LARRY SIMPSON: It’s a pretty idyllic setting right here, isn’t it?

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Mmhmm, the river’s literally sparkling in the sun.

LARRY SIMPSON: It is. This is a special day.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: That’s Larry Simpson, my tour guide. For 20 years, Larry’s been a conservation leader with the Nature Conservancy of Canada…Dedicating his career to protecting places like this in Alberta. This is his favourite place in the whole world. But it’s more than just a beautiful spot. It’s the Last Five Miles. East of the Rocky Mountains, it's the five-mile wide strip of prairie that runs next to them. It's the last part of Canadian prairie that still has most of the large mammals that were once here.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Look at that, like, 10 deer. Oh, they’re all standing up because they see us coming.

LARRY SIMPSON: There’s just more over there, too.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Before European settlement, millions of bison covered this grassland. Many other animals too, including one that might surprise you: the grizzly bear. Today we think of the grizzly bear as a mountain species, but it was once part of the grassland ecosystem. Now, this narrow fringe next to the Rockies is the only place in Canada where you will can still find grizzlies wandering the prairie.

Behind the scenes

(SOUND OF HUMANS WALKING ON GRASS)

TIFFANY CASSIDY: We reach the Waterton River.

(SOUND OF RIVER WATER FLOWING.)

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Larry tells me there’s so much more here than meets the eye.

LARRY SIMPSON: There’s such a richness here and a spaciousness here. Willow and ponds. And the willows oftentimes will feature elk hiding in the spring as they have their calves, or bears hiding as they go to look for those calves if they can find one to feed upon. They’ll have trumpeter swans on some of the lakes. Sandhill cranes who are emitting almost a dinosaur-like sound that you can hardly believe is coming from this bird.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Larry wants me to be able to hear these sandhill cranes before I leave the Eastern Slopes. We might be lucky enough to see some as they pass through on their annual spring migration.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: So how did this last remnant of the northern Great Plains — this refuge for large animals — survive when other areas didn't? Partly because it’s just too rugged to farm; it’s hard to convert the land to cultivate crops. But also because it is perfect for another kind of agriculture. One that’s protecting a delicate balance.

LARRY SIMPSON: The ranch economy is what sustains the space needed by things like bears or cougars, elk, deer or moose.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Ranchers are working with conservationists to protect the land and its wildlife. That may seem counter-intuitive. Don’t grizzlies prey on the cattle? Aren’t they a threat to the ranchers’ livelihoods? Not here.

LARRY SIMPSON: Yes there’s conflict sometimes between bears and people and livestock. And problematic bears are removed from the population. But it’s the ranch economy that keeps that space there so that bears can exist, even in the grasslands region along the edge of the Rockies.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Since 2007, the bear population on the cattle ranches of the Eastern Slopes has increased by four per cent a year.

LARRY SIMPSON: It is certainly an indication of how resilient nature can be.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: The drive into Waterton Lakes National Park is beautiful. And it’s also pretty unique, as parks go. This is the Waterton Park Front. There are no big hotels or tourist attractions along the highway. It's all open ranch land. That’s not by accident. The big threat here is development and fragmentation. It’s a sought-after spot for resort-style vacation and dream homes. That’s why the Nature Conservancy of Canada works with ranchers here. Together, they conserve 82 per cent of the private land that borders the national park. The model works — for ranchers and for nature. We’re going to find out why. We need to meet Tracy Latham.

(SOUNDS OF AN ATV)

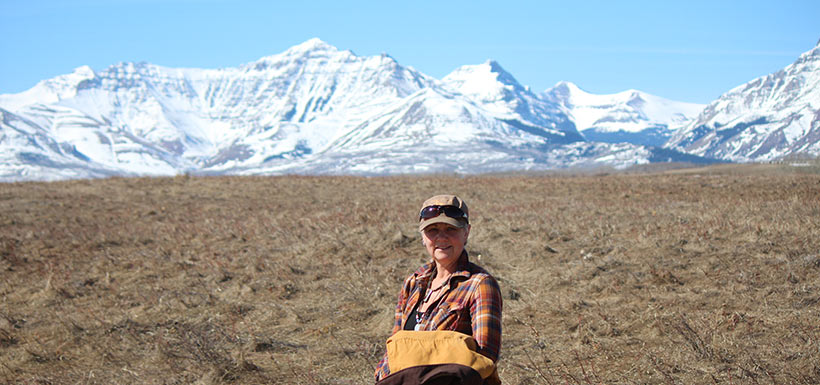

TIFFANY CASSIDY: We’re riding around in an ATV on a ranch with Tracy Latham. Tracy manages this ranch. And we’re heading to one of its most special places to see how wildlife live here.

(SOUNDS OF THE ATV)

TIFFANY CASSIDY: We pull up to one of its most beautiful spots, right in front of a pond.

(SOUNDS OF POND BIRDS)

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Tracy first saw this place when she was a kid.

TRACY LATHAM: I remember gasping at how beautiful it was. And I just felt in my heart that I had to live there. So I guess when you feel something in your heart, you end up going back to it.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Now managing this ranch, she shares it with nature.

TRACY LATHAM: Look, some ducks just landed there. And the moose lives in this pond and she has twins this year. And the cougar sleeps in the lean-to behind the hay shed. So how can you not like that? Geese are flying overhead right now.

(SOUNDS OF GEESE)

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Tracy quickly learned to love the rancher’s life. Specifically, she’s passionate about how ranching can create a better habitat for all animals — that's domestic and wild. We already mentioned that plains bison used to roam wild here. Their grazing was crucial to this functioning ecosystem. It kept these grasses healthy. Today, cattle have replaced bison. Tracy manages the cattle and the range in a way that is good for the land, the grasses and the local economy. So Larry and I hop in a truck with Tracy to see how she does it.

(SOUNDS OF TRUCK DRIVING)

We’re looking for sharp-tailed grouse. That’s one way we can spot healthy grassland habitat. The grouse is funny looking to some, beautiful to others, with a pointy tail and colourful jowls. It lives on the ground. We pull up several metres away from a favourite grouse spot. And we look out.

TRACY LATHAM: So they might be in for the day. Usually in the mornings they’re out here. We could walk over there and see if there’s fresh poop around.

LARRY SIMPSON: Sure!

(SOUNDS OF GETTING OUT OF THE CAR)

(SOUNDS OF WALKING)

TIFFANY CASSIDY: So we head out in search of fresh grouse poop. And we find some…and a few grouse feathers! These birds are here because Tracy allowed her cattle to heavily graze the patch. It creates the exact conditions the grouse need. A few steps away, it’s a different story. LOTS OF GRASS!

TRACY LATHAM: Look at this beautiful grass. Like look at this.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Tracy throws the grass up in the air in excitement.

TRACY LATHAM: Woo! Litter!

TIFFANY CASSIDY: She’s cheering for the old dead grass left over from last fall.

TRACY LATHAM: The grass creates new sod ‘cause it decomposes and becomes beautiful black dirt.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: So this old grass that was left from last year?

TRACY LATHAM: Yeah, like in 10 years it’ll be dirt, but right now it’s keeping all the moisture in the ground below it. So when the new grass shoots up, it’ll come through there and the ground will stay nice and moist, and it’s protecting that new grass.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: That means more grass…for cattle, and also wild elk that will come through here and eat it. Elk are large and magnificent to watch. But you don’t actually have to see them to be impressed.

SOUNDS OF ELK BUGLING

TIFFAN CASSIDY: That’s the sound of a male elk bugling. They put on their best performances in the fall mating season — trying to attract the females. The males will bugle and move slowly towards each other, until they clash antlers in a show of aggression. Best display wins the mate. Their sounds echo across the Waterton Park Front every autumn.

(SOUNDS OF ELK BUGLING)

TIFFANY CASSIDY: This next interview is special. World renowned naturalist Charlie Russell spent a lifetime studying grizzlies. I meet Charlie on the porch of the Hawk’s Nest, his family cabin home perched on a hill overlooking the Waterton Park Front. He grew up here…close to nature.

CHARLIE RUSSELL: You can’t have a childhood like that. It was so ideal. Wandering the mountains with horses. Camping and traveling out from the camps. Watching all the wildlife. Fishing and what have you. It was a beautiful way to grow up. And it established a very important connection with the land, which has kind of haunted me the rest of my life.

(SOUND OF BIRD CHIRPING)

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Charlie’s childhood drove him to be particularly fascinated with grizzly bears. While he grew up, grizzly bears were still being pushed back from a lot of places. He wanted to know more about them. So he observed.

CHARLIE RUSSELL: We insisted that they were this very dangerous animal that had to be killed if we were going to survive. That we couldn’t co-exist. Well I saw evidence that we maybe could co-exist.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Charlie saw on his own ranch that bears rarely killed his cattle. He spent his lifetime observing them and giving them space. And he found the bears were mostly happy to live their lives in landscapes where people lived.

CHARLIE RUSSELL: I had to be a part of nature, and it became such a wonderful experience to immerse yourself into nature as part of it and survive yourself. I became very respectful because nature is a rough place to survive in.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: This was Charlie’s last interview. He passed away two weeks after we met. Charlie’s legacy will be a life lived connected to nature. He worked to build bridges between conservation and ranching here, supporting the development of the Waterton Park Front. For the last time, here’s Charlie’s advice for coexisting with nature:

CHARLIE RUSSELL: Just pay attention to everything. And don’t do it in a superior, with any kind of arrogance or any kind of superiority. Put yourself alone, without your dog, without anything, into nature, and then just start observing and listening and feeling. You’ll develop a tremendous appreciation for the struggle it is for everything to survive.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: To see how these bears and ranchers live together now, we’ll need to talk to someone who shares the space. That’s what we’ll do after the break.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: The Nature Conservancy of Canada is a national charity. We protect important natural areas for the species that need them — species from grass to humans. How much do you know now about ranching and conservation? To answer our quiz and to learn more, go to natureconservancy.ca/podcast. That’s conservancy – not conservatory. Nature c-o-n-s-e-r-v-a-n-c-y.ca.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: We’re travelling around the Waterton Park Front to meet the ranchers who are helping to protect nature. Next stop, the Palmer Ranch.

(BACKGROUND SOUNDS OF THE RANCH)

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Meet Julia Palmer. She’s a third generation rancher on the Eastern Slopes.

(SOUNDS OF A HORSE GALLOPING)

TIFFANY CASSIDY: If she rode her horse over the whole ranch, she would cover 10,000 acres.

JULIA PALMER: One of the things that’s really special about this landscape is that the prairie just kind of comes in and right up to the Rocky Mountains. There’s very little foothills. It’s just basically prairie and then the Rocky Mountains. It's really spectacular. And also very windy (laughs).

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Julia grew up here.

JULIA PALMER: It was the most special place.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: And throughout her life people from other countries came to work on the farm.

JULIA PALMER Everybody’s like [makes wow sound] blown away by it.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: But the fact that it’s so special is one of the reasons why Julia believes in sharing it. Including sharing it with wildlife.

JULIA PALMER: We have to share this space. You know, they’re so magnificent, those large animals. And periodically it causes headaches. We’ve had 500 head of elk come in from Waterton National Park this winter and all of our hay was out in the fields because we were bale grazing. If we hadn’t realized those elk were there, we would have lost our whole hay stack. And so it’s this constant learning how to co-exist. We share this space. And for example with grizzly bears. We’ve been really fortunate. OK, there’s been the odd critter that’s been snacked on, but that’s also part of ranching here. And so, you minimize your risks.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Julia minimizes her risks by picking up dead animals. Her family puts electric fences over their feed piles so the bears can’t get in. She has to be careful…But in the end, ranching is keeping the land healthy and that is allowing wildlife to live here. As Julia grew older, she started to believe she had an important role to play.

JULIA PALMER: I started to view it as a responsibility and view it as an opportunity to leave a little piece of this Earth better, or you know, make a difference in some small way. I’m not the first person who has loved this land. I won’t be the last person who has loved this land. It’s been centuries. It’s sacred territory for the Indigenous community from here. There’s so many people who have loved this place and this place has had meaning for them. And so I am the person who is here now and I hope that I can do well by it. And I want to do well by it. And to me that means that it has to remain intact. It has to remain whole. And one of the best ways for it to be that is to be a working landscape.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Julia’s a bit unique when it comes to ranching. She’s young, turning 33 soon. People her age don’t always stay in ranching. At the same time, people her age aren’t getting into ranching. If you weren’t born onto a generational ranch, you’re unlikely to start. Here’s why. When Julia’s grandfather bought the ranch in the 1980s, it was worth a couple hundred dollars an acre. Now, it’s worth a couple thousand dollars an acre.

JULIA PALMER: A cow won’t pay for that. You cannot make enough money raising beef on that acre of land to justify that expense of buying that land.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: So you need to inherit a ranch to afford to ranch. But if the next generation doesn’t want to continue ranching, the land is at risk of being sold and divided. Instead of being a wide-open space that supports wildlife, it’s broken into many smaller pieces. It becomes fragmented. That means more roads, more houses, more fences…less wildlife.

JULIA PALMER: Habitat fragmentation is really concerning to me. It’s problematic. It changes the landscape. It changes the dynamic of the landscape. And it changes the way people interact with the landscape.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Julia hopes that fragmentation doesn’t have to happen to her ranch. A few years ago, the family sold a part of it — about 5,000 acres — to the Nature Conservancy of Canada, allowing it to be conserved forever. And the family leases the land back for ranching. It was a way to prevent fragmentation. Julia hopes she can also work out something with her family to keep the portion they still own intact and in business for her to ranch into the future. She can’t see herself living anywhere else.

JULIA PALMER: It’s a really beautiful teacher, if that makes any sense. I love that part of it.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Ranching is an important part of what has protected this place for wildlife. Wildlife that needs these big open spaces. And the Nature Conservancy of Canada works with the ranchers to make sure that nature is protected in the best possible way. If ranching continues, this habitat will stay open… And it will protect the wildlife that rely on it.

(SOUNDS OF A CAR DRIVING)

TIFFANY CASSIDY: I’m back on the road with Larry Simpson, winding down our visit to the Eastern Slopes. When suddenly, he pulls over. At the side of the road, sandhill cranes. The birds we’ve been hoping to see. He opens the window, and whispers to me to get out to make sure I can hear them.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: I gotta get out? OK.

LARRY SIMPSON: The sound is just unbelievable.

(SOUNDS OF FOOTSTEPS)

(SOUNDS OF SANDHILL CRANES CALLING)

TIFFANY CASSIDY: There they are: really big grey birds with a red patch on the top of the head. Really long necks and legs. They’ve been seen here for thousands of years.

(SOUND OF SANDHILL CRANES CALLING)

TIFFANY CASSIDY: He’s right. They sound like dinosaurs.

(SOUND OF SANDHILL CRANES FADES)

TIFFANY CASSIDY: The Nature Conservancy of Canada does amazing things — like conserving lands in the last refuge for the original big animals of the Northern Great Plains. This work is only possible because generous people like you donate. If you would like to support this work, go to natureconservancy.ca/podcast and click on the big orange donate button. All amounts make a difference.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Like what you heard on our podcast? Subscribe to future episodes on your favourite app. Give us a tweet [SANDHILL CRANE CALLS] using the hashtag NCC podcast. Share it with a friend. Or email us at podcast@natureconservancy.ca. And if you're looking to explore the amazing places we talk about in this podcast, go to natureconservancy.ca/podcast to see our sites that you can visit.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: Next time, we’re heading further west…to Vancouver Island, and to a meadow that people have cared for over thousands of years. This episode is dedicated to the late Charlie Russel and the community that supports sharing the landscape with the wildlife that live here. Thanks to Charlie, Tracy Latham and Julia Palmer for showing us how they care for nature. Thanks to Larry Simpson for his expertise. And to everyone at the Nature Conservancy of Canada who put this together. And thanks to Pop Up Podcasting. Some of the animals you heard were from the Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, from recordists Dave Herr and Geoffrey A. Keller. And the cool banjo theme music you’re listening to is by NCC staffer/musician Carly Dow.

TIFFANY CASSIDY: I’m Tiffany Cassidy. Thanks for listening.